The real question behind all digital preservation efforts is determining what is worth preserving. Obviously, the incremental cost of digital storage has been falling for years. It is much easier today to simply be expansively eclectic and save everything. You can buy a 1 Terabyte hard drive for less than $50 and jump up to an 8 Terabyte hard drive for less than $140. The price of Solid State Drives (SSDs) is also falling rapidly. In a sense, we can be digital hoarders and save even electronic trivia.

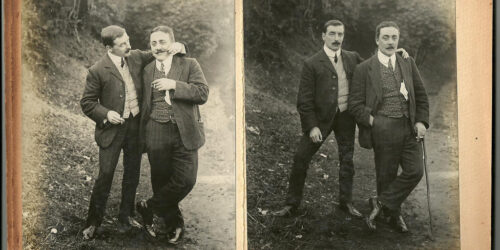

As genealogists, we often have a hard time distinguishing between a “historically and genealogically valuable” document or item and something that has real worth. For example, I have been writing a regular journal for over forty years. Except for the first few years on paper, the entire journal is a series of files on my computer comprised of tens of thousands of pages. Using that document, someone could write a multi-volume book about my life. What are the chances this will ever happen? About zero. Is the journal a valuable historical or genealogical document? I think most historians and genealogists would agree that it is. Oh, I should also mention that my hard drives contain hundreds of thousands of digitized genealogy files including tens of thousands of photos. What about the preservation of the mammoth journal and all the rest?

Well, the answer to that question is the point of this whole series. Presently, I have an entire copy on my main computer which is backed up automatically every few hours during the day. I then have three additional backup hard drives that I use for specific back up areas. The entire computer system including all of the external hard drives is then backed up regularly to a cloud-based storage system.

Where is the weak link in this backup strategy? The weak link is the paywall online backup provider. The simple reason for this, as I have written many times in the past, is that when I become incapacitated or die, who will continue to pay for the online storage or even have access to it? Digital preservation requires active participation by a permanent agency or individual who will make the effort to keep maintaining access to the digitized files.

This is the main difference between our present system of digital preservation and the preservation of analog devices such as paper books is that my paper books can sit on my shelves for years and except for slow, inevitable, chemical changes, they will still be readable in fifty or a hundred years. Granted, someone could throw the books away but almost all of these books are also likely available someplace else in the world. With maybe one or two exceptions, there are no unique items in the thousands of books I have accumulated. Mind you, I am not talking here about some kind of market value. Some “collectible” books obviously have a dollar value but from an information preservation standpoint, a first-edition book has exactly the same value as the millionth copy of the same book. So a book can just sit there and be preserved.

But before you start thinking about reducing all your genealogy to paper, you need to realize that a privately published paper book is not the answer. Remember, when I talk about a book, I am talking about published material that has found its way into perhaps hundreds of libraries. As genealogists. when we base our research efforts on paper, we are creating “unique” documents. One copy of a paper record is in just as precarious position as one digital copy.

This gives us a basic criterion for determining what is worth preserving: uniqueness.

Now it is time to ask, what is necessary to preserve the digital files on my computer’s hard drives?

Digital preservation has two main challenges that are not shared with paper books: device obsolescence and file format obsolescence. Unlike a book sitting on a shelf, a file on a storage media such as a hard drive can become unreadable merely because of the passage of time. This occurs as the devices used to store the information become inaccessible (think floppy disks) or because the operating systems and programs change over very short periods of time (think of an old computer program you can no longer use on any present-day computer).

To preserve the information in a digital file, it must be periodically migrated to newer hardware, programs, operating systems, and file formats as those change over time.

Backing up the files is only the first, small step in preserving them. The files cannot be “left on the shelf.” Every day they sit on your computer, the danger of their loss increases with every incremental change in upgraded operating systems and programs. I have had any number of hard drive failures and it is only because I back up with multiple hard drives and continually buy new hard drives that I can maintain all my information.

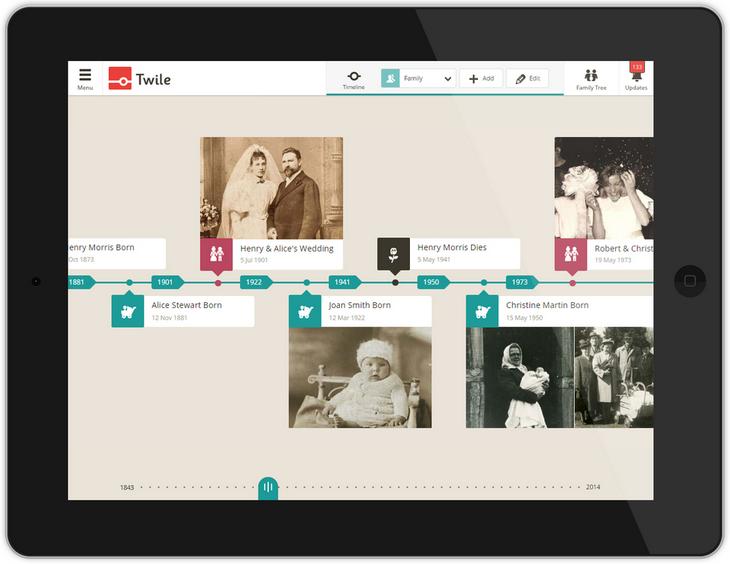

Now a note specifically about genealogy. Your genealogical data should be constantly being transferred to a free, permanently maintained, online database such as FamilySearch.org. If you do nothing else, at least your file information, photos, stories, audio files, and etc. will survive you.

Here is a summary of the process:

1. Acquisition of digital files through direct entry of information or transfer from paper-based documents

2. Maintenance of digital files through multiple layered backup systems involving both local and remote storage

3. Periodic migration of all of the digital files as programs and operating systems change or are upgraded

4. Regular and frequent upgrade of all hardware including the entire computer system.

5. Sharing all information with an online storage entity such as FamilySearch.org.

See the previous posts in this series here:

Part One: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-ultimate-digital-preservation-guide.html

Part Two: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-ultimate-digital-preservation-guide_10.html

Part Three: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-ultimate-digital-preservation-guide_14.html

Part Four: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2019/07/the-ultimate-digital-preservation-guide.html