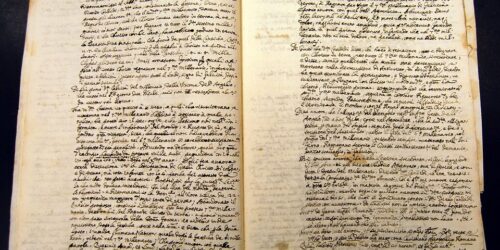

William Shakespeare’s Will by an unknown scribe – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1382708

I can assume that if you have been reading this blog at all previous to this post that you already know something about genealogy. But I am guessing that even some very experienced genealogists have very limited knowledge of paleography. Paleography is the study of ancient writing systems and the deciphering of historical manuscripts. As a genealogist, you may have struggled to decipher old letters and handwritten documents and even done some online indexing but did not know what you were doing was classified as paleography (US; ultimately from Greek: παλαιός, palaiós, “old”, and γράφειν, gráphein, “to write”). The study of paleography goes a lot further back in time than most genealogical research. The earliest handwriting systems evolved independently in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and ancient Mesoamerica. See “A history of writing,” from the British Library.

Inevitably, as genealogists research back in time they encounter the twin problems of deciphering handwriting and translating records in a language they do not know. This is true even if all of your ancestors supposedly spoke the same language you speak today. There is a basic linguistic principle that ll languages evolve or change over time. Although it may appear that from published books that your English speaking ancestors of the early 19th Century spoke a language similar to your spoken English today, it is certain that if you went back in time, you would have trouble understanding them.

Many of us who attended U.S. secondary schools were offered classes in “foreign languages” usually specific European languages such as Spanish, French, or German. Today, here in Provo, Utah grade school children can attend dual language immersion schools in Mandarin Chinese, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. But a year or two of a language usually doesn’t help older genealogists very much. As far as I know, paleography is not formally taught in either primary or secondary schools in the United States. In fact, the teaching of cursive handwriting in the United States has been on the decline for many years but there are some movements to revive its teaching in a very limited way.

When does handwriting in the United States become difficult to read? Almost immediately. Handwriting is very personal and has been used in court cases for years to identify specific people. But some handwriting, even contemporarily written is indecipherable. As you go back in time, almost all the handwriting will start to cause difficulties. Here is an example of a probate document from 1851.

You can click on the document to see the detail.

How do you learn to read old handwriting? It is a learned skill and it takes time and effort. There are quite a few online courses in reading old handwriting both free and paid but there is really no substitution for slowly working your way back through old documents and spending time looking up the words you do not know. Here are some paleography courses to consider.

The Folger Shakespeare Library has links to a large number of websites.

You should also be aware that there are a lot of images of complete examples of alphabets in various handwriting styles. For example, here is an alphabet of the Italic Hand from 1618.

You have to realize that the examples are sometimes the ultimate goal for those learning to write and not particularly helpful with actual handwritten documents. Here is another example of what you might expect in doing research.

The worst case I have encountered in the last few years was found in some parish registers from the 1800s in Puerto Rico. Not only was the handwriting terrible, the ink had faded and the pages were water damaged.