Genealogists who are involved in doing their own original research inevitably run into handwritten documents that are difficult to decipher. The difficulty arises from a number of factors:

- the document is written in a language unknown to the researcher

- the creator of the document had poor handwriting skills

- the document is written in a style of handwriting unfamiliar to the researcher

- the condition of the document makes reading the document difficult or even impossible

- all of those problems exist in the same document making reading the document seem impossible

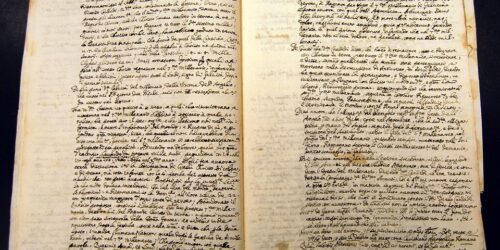

Here is a photo of a document that comes close to being unreadable.

There are several distinct steps to reading a difficult document. The first step is identifying the language and date of the document. Let’s look at one page of the document at the start of this post.

I have circled a few of the places that could cause some problems for someone unfamiliar with this type of handwriting. But we first look at the date, 1779, and the place, the Orphan’s Court of Maryland, before we try to read the text. The first part of this particular document is an indenture (creating and indentured servitude) for a 5-year-old orphan who must serve until he is 21. You can click on the image to see if you can read the items that are circled. You might notice that this handwriting is exceptionally good. However, even if you can read the handwriting, you may not be familiar with the legal language and the format of the document. The rest of the documents are indentures for other orphans.

Let’s go back a hundred or so years to the 1600s. Here is a will from Plymouth County, Massachusetts dated 1664.

This is a little bit more of a challenge. Remember, you can click on the images to see a larger version. Here are the steps in learning to read this handwriting. Many of the letters will be recognizable but it might help to have an alphabet for this same time period. Here is an example of an alphabet for what is called the Old Law Hand and other for Chancery scripts from this book

Court hand restored, or, The student’s assistant in reading old deeds, charters, &c with an appendix, containing the ancient names of places in Great Britain and Ireland: and also, an alphabetical table of ancient surnames. 1778. London: Printed for the Author :;And sold by W. Shropshire.

Here are steps to understanding and reading the old will above.

- Look carefully at the entire document and pick out words or numbers that you can read.

- Start at the beginning of the document and write down all the words you can read. Look carefully at each word and if you cannot read all the letters write down the letters you recognize.

- Go back over the document several times and then look at the alphabet and see if any of the letters you do not recognize match the ones in the document. Do not spend more than an hour, preferably less, looking at the document.

- Put the document away and come back to it, preferably, the next day. Go through the same process again. This time try to fill in the blanks of the parts you could not read the day before. Do not spend more than an hour looking at the document.

- Put the document away for another day and then go through the same process. Look carefully at each of the letters on the alphabet page. You may need to find several alphabet pages like the example above by searching online. It would also help to have a copy of a book such as this one.

Sperry, Kip. 2008. Reading early American handwriting.

In this book there is an appropriate quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Adopt the pace of Nature: her secret is patience. Go through this process over and over again until you have identified all of the words. Lookup any words that are unfamiliar or unknown to you.

The document you produce is called a transcription. If you only record selected portions of the document, it is called an abstract. If the document were in a language you did not read, you would make a translation.

Quoting again from Kip Sperry’s on page 4:

It is important for researchers to transcribe documents and include abbreviations, capitalization, punctuation, original spellings, and marginal additions exactly as they appear in the original. It is acceptable and recommended that you place your interpretation or explanation within square brackets [ ], not parentheses, or use footnotes.

After you have transcribed a few dozen documents from a specific time period, you will probably begin to be able to read the documents without too much difficulty. However, if you move back in time doing research, you will have to start all over again with a new example alphabet and repeat the whole process.

Wills and parish registers are formulaic. That means they repeat the same words in almost every example. So, when you have mastered one will from a particular period of time, you will probably be able to read almost every other will, depending on the writing skill of the creator of the document.

Last, remember the dictionary.

Oh, by the way, I can read the above will. Look at the drawing of the two hands at the end of the will page above the signature.

Here are a few helpful books. Some of these are hard to find.

Bentz, Edna M. If I Can, You Can Decipher Germanic Records. San Diego, Calif.: Tamara J. Bentz, 2011.

Kirkham, E. Kay. The Handwriting of American Records for a Period of 300 Years. Logan, Utah: Everton Publishers, 1981.

Stryker-Rodda, Harriet. Understanding Colonial Handwriting. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co., 2007.