Searching for Clues: When Census and Vital Records Are Not Enough

Growing up as a kid, I loved watching movies about finding lost treasure. The hero usually hears of a legend, finds an ancient artifact or treasure map, and has to follow its clues while fighting off the greedy villain. After a long and difficult struggle, the hero finds the treasure and everything works out in the end! Family history can be a lot like that. Sometimes, the hunt to find information is easy, especially when you can just type in a name and find all the records that you need within the first three pages of search results.

Growing up as a kid, I loved watching movies about finding lost treasure. The hero usually hears of a legend, finds an ancient artifact or treasure map, and has to follow its clues while fighting off the greedy villain. After a long and difficult struggle, the hero finds the treasure and everything works out in the end! Family history can be a lot like that. Sometimes, the hunt to find information is easy, especially when you can just type in a name and find all the records that you need within the first three pages of search results.

However, most often than not, the search is not easy, because records were either lost or recorded differently. For instance, before 1850, United States Censuses only named the head of household and tallied off members of the household by gender and age. Combined with the lack of standardized vital (birth, marriage, and death) records, this can make it very daunting for beginning genealogists—or any genealogists for that matter—to know where to begin if they are researching a family . While there are several other kinds of records that can provide insight for your family, the catch is that often these records were not indexed. This means that searching genealogical websites by names of ancestors may yield no results or findings.

Now, just because these records are not indexed does not mean that they are not available; rather they are found online in catalogs or at physical locations, such as the Family History Library. For example, FamilySearch has an online catalog where you can search by location or type of record. In addition, FamilySearch can inform you on how to access the record, especially if the record is available for research at a Family History Library.

So, what kind of records are available through this catalog that are worth searching through? Here’s a few that can be extremely helpful. Note that not all records are kept in the same way and differ between each state and even cities.

Probate Records: Whenever someone who owns property dies, their estates get evaluated by the local/state courts in a probate case. They determine whether there is a last will and testament, how much their estate was worth, and how it should be distributed or handled. This is a great place to look, as family members are usually involved in the proceedings. Unlike pre-1850 censuses, probate records can give names of family members as well as identify family relationships.

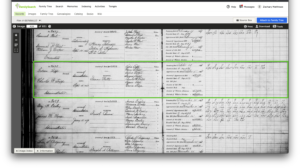

Consider the probate index of Gideon Tripp, one of my wife’s ancestors. Gideon died on 10 August 1868 in Sangamon County, Illinois. His son, Charles W. Tripp, requested the court system to become an administrator of his father’s property. Note here that in this record is a list of family members, with Gideon’s wife, Lydia, and presumably some of their children. For someone who is trying to figure out who Gideon’s family was, this is a great source to look for, especially when you want to get an idea of which children were alive at the time of Gideon’s passing. In addition to that, there is also information of where you can look to read the full probate record and when the probate was administered.

Town Records: Before and during the early days of the United States, local communities often kept records of important events. Usually they consist of council meetings notes and decisions, but they also can list births, marriages, and deaths. This can be a great substitute for official standardized vital records, as well as giving a perspective on how life was for your ancestors.

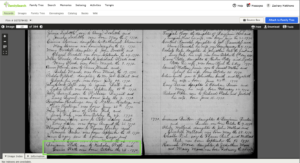

For instance, here are two town records involving Gideon Tripp’s father-in-law, Benjamin Watts. The first one, taken in Warwick, Franklin, Massachusetts, mentions his birth, as shown by the green square, where it identifies his parents and his birth date. The information here is beneficiary to genealogical research.

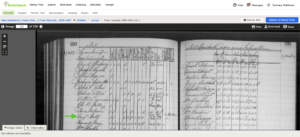

The second one, taken in Lyman, Grafton, New Hampshire, shows an inventory of Benjamin’s livestock and property in 1807. While not as rich in details of identifying family members, this record provides more interesting details into Benjamin’s livelihood and can be a great source for a narrative history.

Land Records: When someone buys land from either the government or another person, a land deed is created. It signifies the previous owner(s), the new owner(s), and the exact boundaries of the land property. This is a great place to look, as it not only can confirm an ancestor’s presence in any given area but can also identify marital relationships.

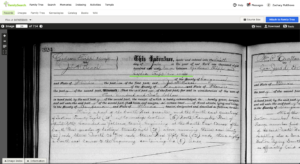

For instance, consider this indenture between Gideon Tripp and John Bench recorded in Sangamon County, Illinois. Notice at the top that Lydia is also included as one of the sellers and is identified as his wife. Considering that no marriage record has yet to be found, this can be a good substitute for indicating their relationship. This also can help us know where exactly in Sangamon County they lived, perhaps with aid from a map.

Of course, there are many other kinds of records available, and the FamilySearch Catalog is not the only place to look. Other libraries and repositories are available for your research, whether by internet or travel. There are so many resources out there, with information and clues about your ancestors. The key is to be persistent and patient. Some days will be long with little to no success, but other days will include amazing discoveries and a better connection with your ancestors. Remember, unlike some treasures in the movies, these people want to be found and have their stories told. And you have that key to unlock it.

Let the hunt begin!